Your Legal Journey.

Unified. Simplified.

Elevated.

One platform connecting Students, Professionals & institutions through learning, mentorship, community, events, and seamless legal opportunities.

Why Legal Lock

Close the Gap: How Legal Lock Fixes What Law School Misses

Legal Lock bridges the critical gaps in legal education, providing the practical tools and guidance that law schools often overlook.

Bridging the Legal Education Gap

The traditional legal education system often leaves students without practical career direction. Legal Lock fills that gap by offering a structured roadmap that transforms theory into real-world readiness.

Beyond Basic Learning: Practical Skills for Real Careers

We don't just provide legal theory. Legal Lock translates what you learn into practical skills that law schools often overlook. You gain the know-how to navigate internships, build your portfolio, and prepare for a successful career.

Personalized Guidance in a Broken System

The current system can feel impersonal. We offer a human touch through mentorship and peer support, ensuring you're not navigating this journey alone.

From Confusion to Confidence: A Real-World Edge

Legal Lock turns confusion into confidence by providing a clear path that law schools don't. When you know exactly what to do next, you gain the confidence to excel in the legal field.

A Single Legal Ecosystem.

Zero Clutter. Maximum Impact.

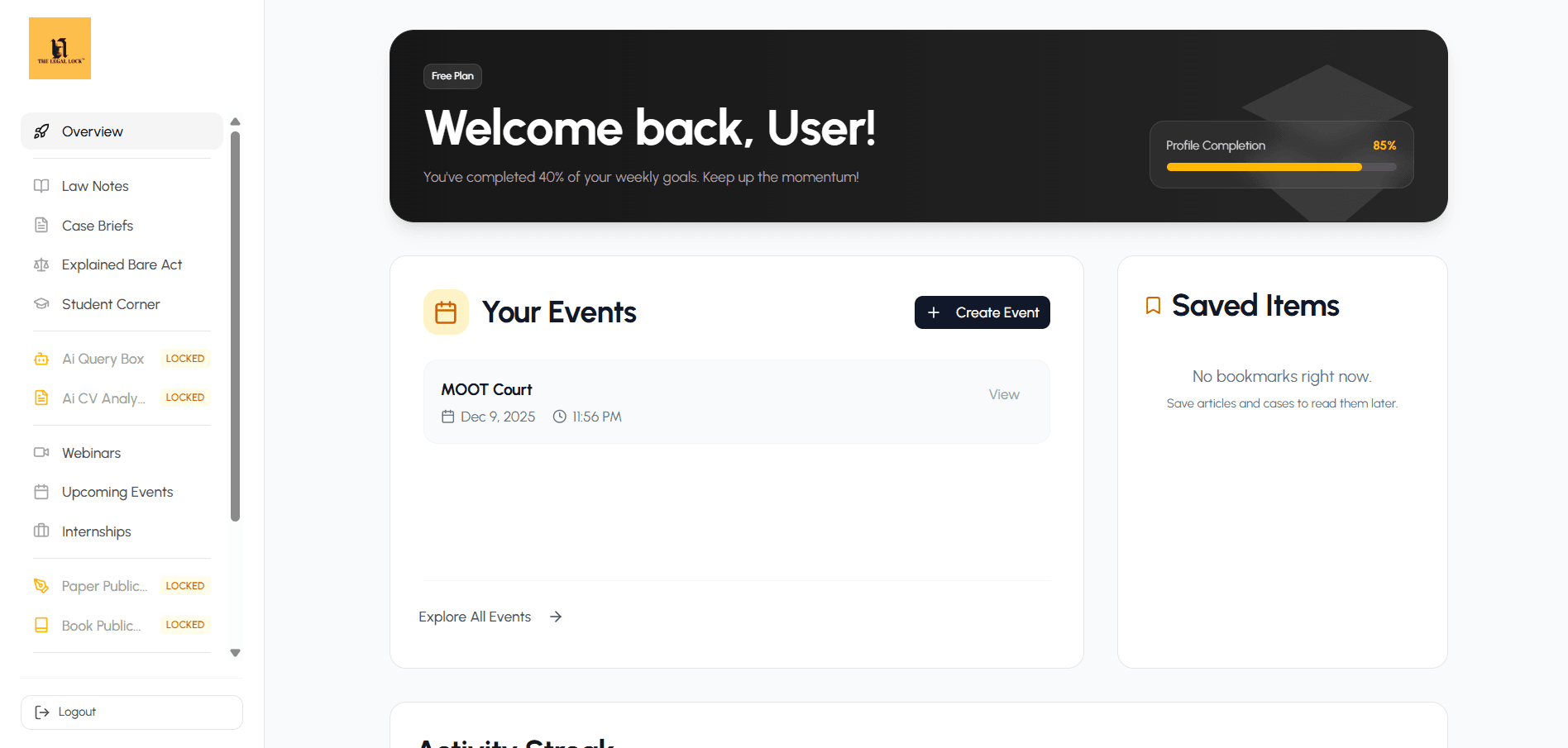

Student Portal

- Foundation courses (1st-3rd year)

- Advanced modules (IBC, Communication, AOR etc)

- Publications & research support

Professional Portal

- Become a mentor

- Host masterclasses / paid sessions

- Publish expert articles

- Get featured in The Legal Lock panel network

Institutional Portal

- Institutional subscriptions

- Student development programs

- Guest lectures & panel collaborations

- Marketing and media support

Our Advisory Panel

Guided by industry veterans and academic leaders shaping the future of legal education.

Ready to Transform Your Legal Journey?

Join thousands of law students and professionals who are already using The Legal Lock to excel in their careers.